History

130 YEARS SINCE THE FOUNDING OF THE JUDICIAL POWER IN VARNA AND 10 YEARS SINCE THE RESTORATION OF THE COURT OF APPEALS

The ideas about the Bulgarian national judicial system started forming as early as during the process of the national liberation movement. For the first time, the matter was raised in Sofroniy Vrachanski’s note which he presented to Kutuzov in 1811 in Bucharest. Later, the exposition of Neofit Bozveli to the Sublime Porte from the 1840s also contained views on the future organization of the judicial system. The activists of the Bulgarian Secret Central Committee, an organization behind the national liberation movement, created the so-called Memoirs, another document dealing with suggestions regarding the future judicial system. Such ideas were developed also by Prince Gorchakov.

Information about the opinions of the Bulgarians regarding the organization of the judicial system is contained in “Les voeux des bulgares” in №27 / December 9, 1876, and the desires of the Bulgarian nation in “Les voeux de la nacion bulgare” in № 4 / December 16, 1876. These documents were found by Acad. Hristo Hristov in the archives of the Marquess of Salisbury, a representative of the United Kingdom at the Six Powers’ conference in Constantinople (Istanbul). They reveal for the first time the intention to create a Supreme Judicial Council to consist of all chairmen of appellate courts and to be run by the chairman of the Supreme Judicial Council. On the eve of the Constantinople Conference, other projects were also presented – that of the Secretary of the American legation in Constantinople, Eugene Schuyler and Prince Alexey Tseretelev. The project on the terms of the peace developed at the ambassadors’ conference also reports on ideas about the organization of the Bulgarian judicial system.

During the period of the temporary Russian governance, as per Prince Cherkassky, and later, according to Prince Dondukov-Korsakov, the change of the judiciary had to be conducted after “a careful investigation of the local conditions”.

During the Liberation, the Bulgarian municipalities continued their judiciary activities which they had carried out before that by applying the Bulgarian legal customs. Restored were also the so-called councils of the elders - the oldest form of Christian courts that each village had. They had 3 to 12 elected members and the process they applied was mediatory – amicable.

On August 24, 1878, Prince Dondukov-Korsakov confirmed the Temporary Rules regarding the organization of the judiciary power in Bulgaria the development of which started back under Prince Cherkassky. Their confirmation was carried out by Prince Dondukov and they were translated into Bulgarian by a commission chaired by Todor Burmov from Plovdiv. The basic principle was to adhere to the Bulgarian tradition and to avoid redundant novelties.

The district courts pursuant to the Temporary Rules regarding the Organization of the Judiciary Power were established in each administrative district. They consisted of a chairman, 3 permanent and 12 elected members. The judges and the chairman were appointed while the elected members were elected in two-stage elections. They reviewed civil lawsuits, criminal cases as per the not-yet-abolished Ottoman criminal law and acted as trial courts.

Varna is the last city liberated during the Russian-Turkish war on July 27, 1878 and was chosen as a center of a province during the month of May of the same year. At that point was appointed the first governor of Varna – Pavel Baumgarten.

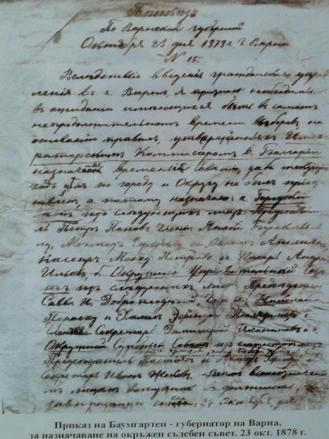

On October 23, 1878, by order of the governor Baumgarten were appointed the first Bulgarian administrative and judicial powers. Veliko Hristov was appointed as chairman of the District Judicial Council of Varna. Ivan Zhekov was the first secretary and there were also two members. This set the beginning of the judiciary activity in the Varna judicial region. From January 01, 1879, Varna province covered the Varna, Provadia, Balchik, Shumen, Silistra and Hadjioglupazardjik districts and a district courthouse was constructed in each of them. All civil, commercial and criminal cases were actionable in those courts.

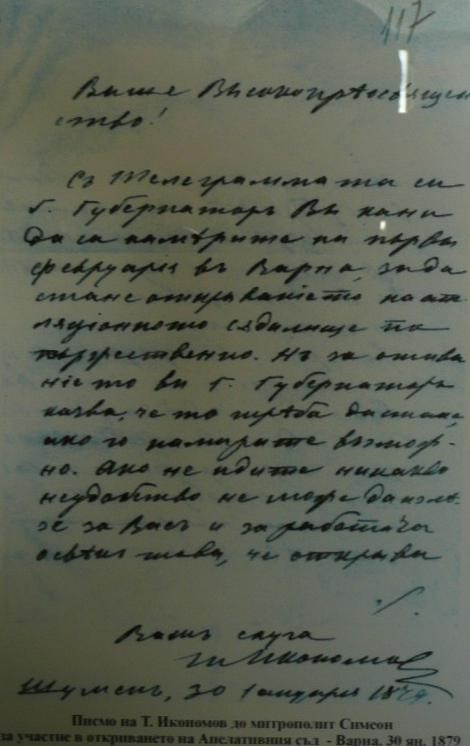

On February 01, 1879, the Court of Appeals opened its doors with Yakov Gerov as chairman. The letter of Todor Ikonomov to Simeon, the Metropolitan of Varna and Preslav, bears witness to the formality of the opening ceremony and also to the respect for and deference to the institution. In his letter, Ikonomov invited the metropolitan to the inauguration of the “appellate courthouse on January 30, 1879. At that time, the metropolitan was elected to participate in the work of the Founding National Assembly in Tarnovo. Other participants there by right were the chairmen of all district courts as well as of the Varna court of appeals, Yakov Gerov. Since the first chairman of the District Judicial Council, Veliko Hristov, was elected as mayor of Varna, a new chairman had to be elected and that was Georgi Velchev. This can be seen from the list of members of the Founding Assembly in Tarnovo which reviewed the Organic Judicial Statute. The documents preserved from those days testify to the high trust in and respect for the judicial system and in particular the court chairmen that society had in those days.

The Temporary Rules in the provinces were used as guidelines also to build the administrative courts. Thus, in Varna was also established an Administrative Court chaired by Dimiter Ikonomov. A Commercial Court was founded as well, chaired by Dimiter Statelov which existed until 1880. Pursuant to a decree from August 20, 1880, only two appellate courts remained in the principality – in Ruse and Sofia. After the Unification, they were joined by the appellate court in Plovdiv.

From its very founding, the Varna district court had two divisions – civil and criminal. The court was composed of a chairman, a deputy chairman, three members, a secretary, two assistant secretaries, two scribes, three couriers who were appointed by the Prince and the Ministry of Justice as well as honorary members who were picked by ballot to participate in the court hearings. This organization was kept in place until the passing and publication of the first Act on the Organization of the Courts, promulgated in the Darzhaven Vestnik state gazette, issue 47 from June 2, 1880.

The judges in those days had to suffer sacrifices and harassment as part of asserting their independence. The memoirs of Dimiter Statelov, a judge in the Varna District Court from 1878 to 1879, state: “In 1878, Dragan Tsankov was appointed governor in Varna. He wanted as (some pasha) to review some civil or criminal cases, yet soon I made it clear to him that this was not his business. Because I did not give the governor to review several cases, upon his insistence I was moved to Provadia – to the district court.”

There is another judge from Varna, Georgi Pasarev, who writes about upholding the principle of separation of powers already argued by Montesquieu in Spirit of Laws. In 1890, Georgi Pasarev graduated in law in France and at 24 started working at the Varna district court. He tells us about an Inquiry Committee to the National Assembly which banned all notaries from carrying out sales of the real estate of Stefan Stambolov. The Sofia district court pronounced with a ruling that an inquiry committee was not allowed to pass a judgment on this issue and that it is mandatory to observe the principle of separation of powers. “The Sofia appellate court confirmed the ruling of the first instance court and thus for the first time,” Pasarev writes, “the rights of the citizens were defended from the encroachment of the other powers.”

Georgi Pasarev in his memoirs also touches on the issue of the independence of the court during the so-called regime of capitulations. Then “the consuls оf the other subjects as a result of the capitulations wanted to interfere into the system of justice.” Further, he writes that most proper was the conduct of the English consuls who “never sent a clerk of their own to attend the hearings of cases of their subjects in court.”

In these memoirs, we encounter valuable evidence about the process of administering justice. Again in the recollections of Dimiter Statelov, we read: “The practitioner judges exhibited great industriousness, researched the cases rather well, prepared thorough reports and administered justice rather well. On the whole, they behaved with respect and dignity. In terms of procedural statutes, we had Temporary Judicial Rules. We looked up the Russian compositions in legal sciences and the compositions of the western countries - if there was a judge who had studied in the West. The public, the citizens treated with reverence the courts and the judges in society. The courthouses were modest but decently appointed. The judges were a relatively united institution and well reimbursed.” In particular, Statelov notes that they received 400 francs monthly in rubles of 3 ½ francs in Napoleon coins during 1878.

“The position of a judge was preferred,” Georgi Pasarev writes in his memoirs, “because that of a prosecutor exposed the holder to the powerful governmental partisans and specially before the administration.”

Pasarev continues: “The powerful governmental partisans tried to put pressure on the judges yet in most cases the effect was the opposite. The judges defied such actions. Often, there were conflicts between the courts and the administration which derived from the weak education of the persons occupying the top positions and the flawed idea they had about the judiciary institution. The Ministry of Justice defended the judges to the extent that was possible, specifically if the Minister of Justice had power in the Cabinet. Even if there was no Law yet on the irremovability of judges when the minister of justice was Slavkov from Tarnovo, they were practically irremovable. Slavkov had a strong position in the Cabinet and was not influenced by governmental partisans.”

According to Prof. Tokushev, “History of the Bulgarian State and Law”– 1878 – 1944, p. 138, Sibi, 2001 we have: “The development of the legislation for the work of the judicial power indicates that the judges were not guaranteed the irremovability that was established later. Even if it defended the independent judges from the arbitrariness of the executive branch, the legislator always changed the status of the judges when this was called for, without bringing forward any arguments.”

Alexander Diakovich, chairman of the Varna District Court from 1888, writes in his recollections: “The Bulgarians judges had to resort to foreign materials and the courthouses had no libraries. We had to make do, out of necessity, with what could be found here and there, as bees wandering around in search of pollen from one herb to another, in order to resolve some dispute. The judges always resolved it with the complete conviction, cemented in the absence of laws and folk customs – through the efforts of high fairness.

“Not all judges at the time had legal education yet all without reserve were devoted to their post and served ideally and with abnegation to the Bulgarian judicial cause. They truly acted as though they performed a religious rite, even if not clad in Roman togas. And not only did they have the respect of the administration domestically but also abroad. So soon, the foreign countries started talking with respect about Bulgaria. The capitulations were withdrawn, initially implicitly and later also explicitly.”

These examples bear witness to the high level of conscientiousness and professionalism of our predecessors and to the respect society had for them and for the work of the judicial institution.

The history of the judicial practice in Varna includes one of the worthiest names with a remarkable contribution to the establishment of the new Bulgarian administration, i.e. that of Krastio Mirski. He chaired the Varna District Court from July 1, 1880 to May 30, 1881 and was revered both as a citizen of Varna and a mayor of the city.

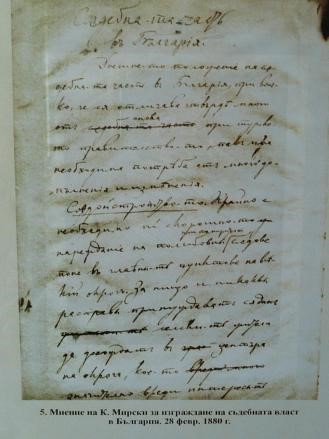

Preserved are his Notes on the changes in the organization of the judicial power in Bulgaria, recorded in a letter to the minister of justice: “The situation nowadays of the judicial branch in Bulgaria features the fundamental need of many additions to and modifications of the judiciary, in the Civil proceedings and the Criminal proceedings. It necessitates also an improvement of the staff, of the chairmen and the court members. All officials in the court should be appointed on a competitive basis. Once accepted, they should be well provided for, reprimanded for the smallest offense, and for each crime to be taken to court and then fired…”

Preserved is also a Decree referring to the justices of the peace from 1880. It is issued in Varna in the St. Dimiter monastery in Evksinograd on August 15, 1880 by Prince Alexander of Battenberg.

In the series of names of chairmen of courts, we come across the name of the writer Stoyan Mihaylovski, of Alexander Diakovich etc. It is precisely Diakovich who worked on a project of a criminal act assigned to him by Dr. Konstantil Stoilov after the project was rejected by the commission headed by the Frenchman Bastien. Diakovich’s project was accepted. His Criminal Act adhered to all contemporary European acts. It came into force in 1896 and was in effect until 1951.

The judges went to great pains to learn the Temporary Judicial Rules. Each evening they gathered to study them and they did have to study a lot as the book was rather thick, of about 1,000 pages.

130 years later, we, the Bulgarian judges of today, are again confronted with challenges similar to those of our predecessors. Our efforts today to assimilate the European law are commensurate with those of our forerunners.

The history of the courts in Varna is replete with the actions of highly respected judges who constantly tried to perfect themselves within the limits of what the times allowed and who upheld their independence. With hard work, they achieved high professional success, asserted the independence of their actions and left us an estimable example worthy of imitation.

One of the explorers and champions of the judicial cause in Varna, Assoc. Prof., Dr. Masis Hadzholian who is the former head of the Regional and District Prosecutor’s Office says in his Memoirs of the judicial system in Varna during the second half of the 20th century: “As followers of our predecessors, it is good for us to look back to the past, to assess from the distance of the years the events of those times, to make sense of the present and thus to look into the future. We are supported by the inevitability of a development based on the effort and experience of the inexhaustible human generations.”

The history of the judiciary in Varna, of the courts founded and functioning 130 years ago as one of the first newly established state institutions in Bulgaria is yet another powerful expression of the deeply inborn respect the Bulgarians have for the truth and justice. And of the distinct awareness that the State is unthinkable without the lawful order. I believe that the work of the predecessors and the created traditions have their worthy continuation in the work of the judges of the area of the Court of Appeals also in the 21st century.

VIOLETA BOYADZHIEVA

CHAIRPERSON

COURT OF APPEALS

VARNA

/ 2004-2013/